NEWS

Tourists from all over the world come to visit the Bikan Historical Quarter in Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture, and it is as popular a destination today as ever. The history of this area’s development, however, is full of dramatic twists and turns.

An almost total lack of industry in the Meiji era

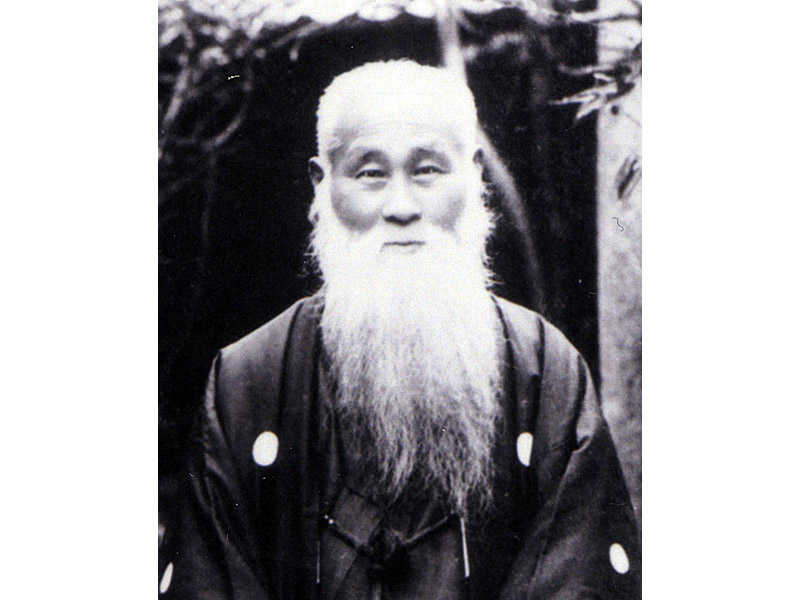

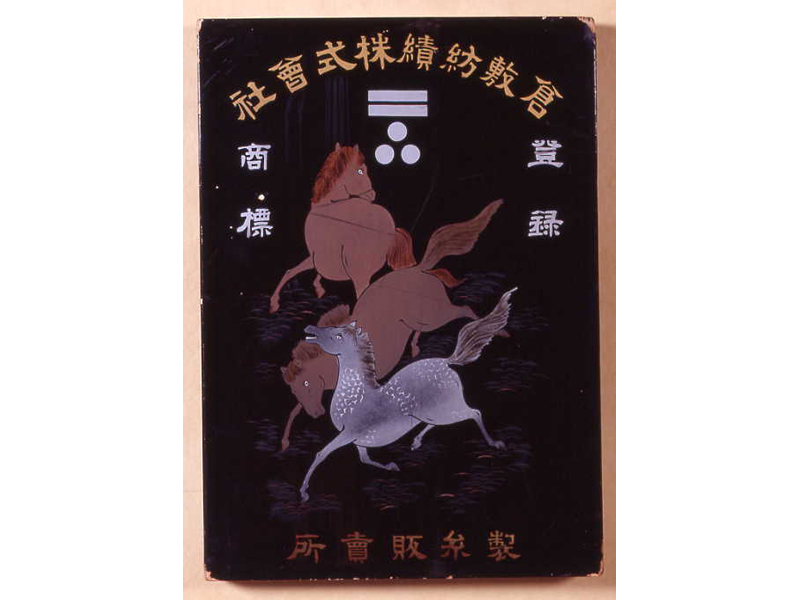

Kurashiki is one of Japan’s most popular tourist spots, but back in the Meiji era, there was no industry to speak of aside from rice and cotton. Infectious disease and crop failures sapped the spirit of the village during the late 19th century, until three young men from the village decided to set up a cotton mill to get the economy moving again. They reached out to the local movers and shakers of the day for help. With the aid of numerous people, Koshiro Ohara managed to establish Kurashiki Spinning Works, the precursor to Kurabo, in 1888. He would also serve as its first company president.At the time, cotton mills in Japan made use of dated machines known as “spinning mules”. Kurabo, however, adopted ring spinning machines—which were cutting-edge technology back then. In just a few short years, the company was turning out premium yarn. Kurabo later expanded its business by exporting cotton yarn to China under the brand name Mitsuuma.

Why did the company change working conditions so dramatically?

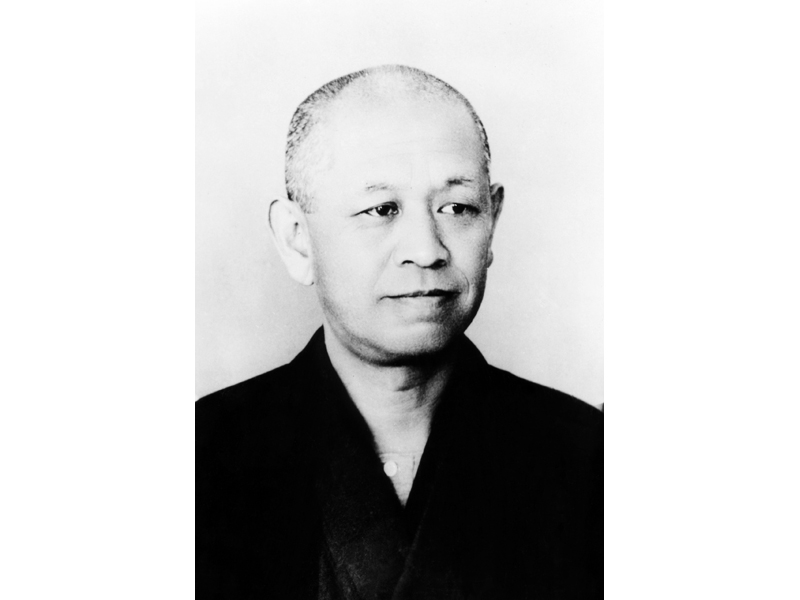

In 1906, Magosaburo Ohara succeeded Koshiro as the company’s second president. Soon after, he began initiating sweeping reforms to employee working conditions. Cotton mills in those days typically subjected employees to brutal hard labor with few breaks—with large open-room dormitories serving as breeding grounds for tuberculosis and other diseases. Kurabo responded by eliminating the open-room dorms where a thousand of its workers were housed, instead constructing family-style divided housing units. They improved health and sanitation further by providing their employees with fully-equipped dining halls, public baths, a clinic, and other facilities. In addition, because most of their employees did not even have an elementary school education, classrooms were set up inside the factory. With these reforms, the company made it its mission to support healthy living and academic study.

“I’m always looking ten years ahead”

Magosaburo Ohara was a visionary man who was fond of saying, “I’m always looking ten years ahead.” It was his ability to run the business in anticipation of future changes that allowed him to expand so successfully. At the end of the Meiji era, he had moved his base of operations to Osaka and diversified the company’s business activity. These and other audacious moves often triggered fierce opposition among Kurabo executives and stockholders.Magosaburo Ohara was constantly translating his ideals into reality. He would later remark, “When starting a new project, if two or three people out of ten want to go along with it, it’s time to get moving. If not a single person wants to go along with it, it’s still too soon. But if five people are on board, you’ve already gotten a late start. Once seven or eight of ten agree with you, you’d better scrap the entire thing.” His passion for anticipating the future and doing whatever it took to solve cutting-edge social issues is woven into Kurabo’s corporate DNA and drives our business practices even today.

“I’m always looking ten years ahead”

Magosaburo Ohara established numerous facilities in Kurashiki that are still widely known today, among them the Ohara Museum of Art and the Institute of Plant Science and Resources, which helped establish peaches and grapes as specialty crops in Okayama Prefecture. He was also instrumental in the establishment of Kurashiki Central Hospital, which is one of the largest hospitals in Western Japan. Kurashiki Ivy Square, a renovated and restored Meiji-era cotton mill, is also a popular sightseeing and overnight destination. The legacy of Kurabo thus lives on in many local Kurashiki industries still today.